The Muslims Fought Again Whom John Calvin

Protestantism and Islam entered into contact during the early-16th century when the Ottoman Empire, expanding in the Balkans, first encountered Calvinist Protestants in present-solar day Hungary and Transylvania. Every bit both parties opposed the Austrian Holy Roman Emperor and his Roman Catholic allies, numerous exchanges occurred, exploring religious similarities and the possibility of trade and military alliances.

The early Protestants and Turks established a sense of mutual tolerance and understanding, despite theological differences on Christology, because each other to be closer to i another than to Catholicism.[ane] The Ottoman Empire supported the early Protestant churches and contributed to their survival in dire times. Martin Luther regarded the Ottomans equally allies against the papacy, considering them the "rod of God'due south wrath against Europe'due south sins."[2] The allegiances of the Ottoman Empire and threat of Ottoman expansion in Eastern Europe pressured King Charles V to sign the Peace of Nuremberg with the Protestant princes, accept the Peace of Passau, and the Peace of Augsburg, formally recognizing Protestantism in Frg and ending military machine threats to their beingness.[three]

Introduction [edit]

Protestantism is a branch of the monotheistic Christian organized religion which originated in Europe in the early 16th century. Information technology adheres doctrinally to the doctrine of the Holy Trinity and other theological doctrines of the Catholic Church and the Eastern Orthodox Church, but split from the Western (Roman) Cosmic Church building as a "Protest" against ecclesiastical corruption, pastoral abuses and certain doctrines of the Roman Cosmic Church building. Protestantism itself had multiple variations from the start, specifically amidst followers of Martin Luther, John Calvin, Huldrych Zwingli and subsequently, Thomas Cranmer.

Islam is a monotheistic religion, arising around 600 Ad, that considers itself the concluding accurate practice of the faith of the patriarch Abraham. While it is Abrahamic, it presents views of Jewish scripture (the Tanakh) and of Jesus that are incompatible with Judaism and Christianity, respectively.

The bailiwick of this page is to consider the historical political, armed services, and cultural/religious interactions of Protestant and Islamic rulers.

The majority of this page examines a hypothesis that Protestant states and the Islamic Turkish state acted to align themselves based on various common interests.[ original inquiry? ] 1 aspect of this hypothesis posits that, in the 16th and 17th centuries, Turkish and Protestant rulers shared a common geopolitical opposition to the Roman Catholic Holy Roman Empire, and tensions with France and Spain, the other large Roman Catholic states, and that this common interest gave ascent to alignment in political and military machine alliances. It is also discussed whether Protestantism and Islam aligned theologically on iconoclasm, and, culturally—in terms of the religiously-motivated cultural mores of that era – in opposition to the person or office of the Roman Catholic Pope.

Historical background [edit]

Protestantism and Islam entered into contact during the 16th century when Calvinist Protestants in nowadays-day Republic of hungary and Transylvania coincided with the expansion of the Ottoman Empire in the Balkans. As Protestantism is divided into a few distinguishable branches and multiple denominations within the sometime, it is hard to determine the relations specifically. Many of these denominations tin can take a different approachment to this affair. Islam is divided besides into diverse denominations. This article focuses on Protestant-Muslim relations, but should be taken with caution.

Relations became more adversarial in the early modernistic and modernistic periods, although recent attempts have been fabricated at rapprochement. In terms of comparative faith, in that location are interesting similarities especially with the Sunni, while Catholics are oftentimes noted for similarities with Shias,[4] [5] [6] [vii] [8] [9] likewise as differences, in both religious approaches.

Following the Ottoman conquest of Constantinople in 1453 by Mehmed the Conqueror and the unification of the Middle East under Selim I and his son Suleiman the Magnificent managed to aggrandize Ottoman rule into Central Europe. The Habsburg Empire thus entered into direct conflict with the Ottomans.

At the same time the Protestant Reformation was taking place in numerous areas of northern and central Europe, in harsh opposition to Papal authority and the Holy Roman Empire led by Emperor Charles V. This state of affairs led the Protestants to consider various forms of cooperation and rapprochement (religious, commercial, military) with the Muslim earth, in opposition to their common Habsburg enemy.

The Ottoman Empire shared a boundary with Christian Europe to the southeast, engaging into contact with Calvinist, Lutheran and Unitarian minorities. This map shows the spread of Protestantism in the 16th and 17th centuries, superimposed on modern borders.

Early religious accommodation (15th–17th centuries) [edit]

A map of the rule of the Habsburgs post-obit the Battle of Mühlberg (1547) as depicted in The Cambridge Modern History Atlas (1912); Habsburg lands are shaded green. Not shaded are the lands of the Holy Roman Empire over which the Habsburgs presided.

During the development of the Reformation, Protestantism and Islam were considered closer to each other than they were to Catholicism: "Islam was seen as closer to Protestantism in banning images from places of worship, in not treating marriage every bit a sacrament and in rejecting monastic orders".[1]

Common tolerance [edit]

The Sultan of the Ottoman Empire was known for his tolerance of the Christian and Jewish faiths within his dominions, whereas the King of Spain did not tolerate the Protestant faith.[10] The Ottoman Empire was indeed known at that time for its religious tolerance. Various religious refugees, such as the Huguenots, some Anglicans, Quakers, Anabaptists or even Jesuits or Capuchins were able to notice refuge at Istanbul and in the Ottoman Empire,[11] where they were given right of residence and worship.[12] Farther, the Ottomans supported the Calvinists in Transylvania and Hungary simply also in France.[eleven] The contemporary French thinker Jean Bodin wrote:[eleven]

The cracking emperor of the Turks does with as great devotion equally any prince in the earth honour and observe the religion by him received from his ancestors, and yet detests he non the foreign religions of others; but on the contrary permits every homo to live according to his conscience: yep, and that more is, near unto his palace at Pera, suffers 4 various religions viz. that of the Jews, that of the Christians, that of the Grecians, and that of the Mahometans.

Martin Luther, in his 1528 pamphlet, On War against the Turk, calls for the Germans to resist the Ottoman invasion of Europe, as the catastrophic Siege of Vienna was lurking, but expressed views of Islam which, compared to his ambitious spoken language against Catholicism (and later on Judaism), are relatively mild.[thirteen] Concerned with his personal preaching on divine atonement and Christian justification, he extensively criticized the principles of Islam as utterly despicable and cursing, considering Qu'ran as void of any tract of divine truth. For Luther, it was mandatory to let the Qu'ran "speak for itself" as ways to evidence what Christianity saw equally a draft from prophetic and churchly teaching, therefore allowing a proper Christian response. His cognition on the field of study was based on a medieval polemicist version of the Qu'ran made by Riccoldo da Monte di Croce, which was the European scholarly reference of the subject. In 1542, while Luther was translating Riccoldo's Refutation of the Koran, which would become the first version of Koranic cloth in German, he wrote a letter to Basle's metropolis council to relieve the ban on Theodore Bibliander's translation of the Qu'ran into Latin. Mostly due to his letter, Bibliander'south translation was finally allowed and somewhen published in 1543, with a preface made past Martin Luther himself. With admission to a more accurate translation of the Qu'ran, Luther understood some of Riccoldo'southward critiques to be partial, simply nevertheless concurred with virtually all of them.[14]

Preface of Martin Luther of Bibliander's translation of the Qu'ran in Latin.

Equally a religious profession, however, Luther felt the same sense of tolerance for freedom of conscience to be given to Islam as to other faiths of its time:

Let the Turk believe and alive as he will, just as i lets the papacy and other false Christians live.

—Excerpt from On state of war against the Turk, 1529.[xv]

Nevertheless, this statement mentions "Turks", and it is not clear whether the meaning was of "Turks" as a representation of the specific dominion of the Ottoman Empire, or every bit a representation of Islam in general.

Martin Luther'due south reasoning besides appears in one of his other comments, in which he said that "A smart Turk makes a better ruler than a dumb Christian".[xvi]

Efforts at doctrinal rapprochement [edit]

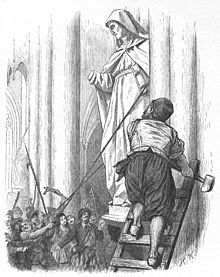

Iconoclasm: The organised devastation of Catholic images swept through Netherlands churches in 1566.

Martin Luther likewise took note of the similarities between Islam and Protestantism in the rejection of idols, although he noted Islam was much more drastic in its complete rejection of images. In On War against the Turk, Luther is really less critical of the Turks than he is of the Pope, whom he calls an anti-Christ, or the Jews, whom he describes equally "the Devil incarnate".[13] He urges his contemporaries to also run into the skillful aspects in the Turks, and refers to some who were favourable to the Ottoman Empire, and "who actually want the Turk to come and rule, because they think that our German language people are wild and uncivilized - indeed that they are half-devil and half-homo".[12]

The Ottomans besides felt closer to the Protestants than to the Catholics. At one point, a alphabetic character was sent from Suleiman the Magnificent to the "Lutherans" in Flanders, claiming that he felt close to them, "since they did non worship idols, believed in one God and fought against the Pope and Emperor".[17] [15]

This notion of religious similarities was again taken up in epistolary exchanges betwixt Elizabeth I of England and Sultan Murad III.[18] In one correspondence, Murad entertained the notion that Islam and Protestantism had "much more in mutual than either did with Roman Catholicism, equally both rejected the worship of idols", and argued for an brotherhood between England and the Ottoman Empire.[19]

In a 1574 letter to the "Members of the Lutheran sect in Flanders and Spain", Murad III fabricated considerable efforts to highlight the similarities between Islamic and Protestants principles. He wrote:

As you, for your part, practice not worship idols, y'all have banished the idols and portraits and "bells" from churches, and alleged your faith by stating that God Omnipotent is one and Holy Jesus is His Prophet and Retainer, and now, with center and soul, are seeking and desirous of the true faith; but the faithless i they call Papa does not recognize his Creator as One, ascribing divinity to Holy Jesus (upon him be peace!), and worshiping idols and pictures which he has made with his own hands, thus casting doubt upon the oneness of God and instigating how many servants to that path of error.

—1574 alphabetic character of Murad 3 to the "Members of the Lutheran sect in Flanders and Spain".[20]

Such claims seem to have been politically inspired every bit well, with the Ottomans trying to establish religious mutual ground as a way to secure a political alliance.[20] Elizabeth I herself however made efforts to adapt her ain religious rhetoric in order to minimize differences with the Ottomans and facilitate relations.[21] In her correspondence with Murad, she stresses the monotheism and the anti-idolatry of her faith, by uniquely describing herself as:

Elizabeth, by the grace of the most mighty God, the 3 part and yet singular Creator of Heaven and World, Queen of England, France and Ireland, the most invincible and most mighty defender of the Christian faith against all the idolatry of those unworthy ones that live amongst Christians, and falsely profess the name of Christ

—Letter of the alphabet of Elizabeth I to Murad 3.[22]

Armed forces collaboration [edit]

Military cooperation between the Ottoman Empire and European powers started in earnest with the Franco-Ottoman alliance of 1535. The brotherhood provided strategic support to, and effectively protected, the kingdom of France from the ambitions of Charles V. It also gave the opportunity for the Ottoman Empire to become involved in European diplomacy and proceeds prestige in its European dominions. Side effects included a lot of negative propaganda against the actions of France and its "unholy" alliance with a Muslim power. According to historian Arthur Hassall the consequences of the Franco-Ottoman brotherhood were far-reaching: "The Ottoman alliance had powerfully contributed to save French republic from the grasp of Charles 5, it had certainly aided Protestantism in Germany, and from a French bespeak of view, it had rescued the North German language allies of Francis I."[23]

Even after the 1571 Boxing of Lepanto Ottoman support for France would continue even so, every bit well as support for the Dutch and the English after 1580, and support for Protestants and Calvinists,[17] as a fashion to counter Habsburg attempts at supremacy in Europe.[17] Various overtures were made by Ottoman rulers to the Protestants, who were also fighting against a common enemy, the Catholic Firm of Habsburg. Suleiman the Magnificent is known to take sent at least one letter to the "Lutherans" in Flemish region, offering troops at the fourth dimension they would asking,[24] Murad III is besides known to have advocated to Elizabeth I an brotherhood between England and the Ottoman Empire.[19]

Overall, the armed services activism of the Ottoman Empire on the southern European front probably was the reason why Lutheranism was able to survive in spite of the opposition of Charles V and attain recognition at the Peace of Augsburg in September 1555:[sixteen] "the consolidation, expansion and legitimization of Lutheranism in Frg by 1555 should be attributed to Ottoman imperialism more than to any other unmarried factor".[25]

The Dutch Revolt and Islam [edit]

Fundamentally, the Protestant Dutch had strong antagonisms to both the Catholics and the Muslims. In some cases even so, alliances, or attempts at alliance between the Dutch and the Muslims were made possible, every bit when the Dutch allied with the Muslims of the Moluccas to oust the Portuguese,[26] and the Dutch became rather tolerant of the Islamic faith in their colonial possessions afterward the final subjugation of Macassar in 1699.[26]

During the Dutch Revolt, the Dutch were under such a drastic situation that they looked for aid from every nationality, and "indeed even a Turk", equally wrote the secretary of Jan van Nassau.[27] The Dutch saw Ottoman successes confronting the Habsburgs with slap-up involvement, and saw Ottoman campaigns in the Mediterranean as an indicator of relief on the Dutch front. William wrote around 1565:

The Turks are very threatening, which will hateful, we believe, that the king volition not come up to the netherlands this year.

—Letter of the alphabet of William of Orange to his brother, circa 1565.[27]

The Dutch looked expectantly at the development of the Siege of Malta (1565), hoping that the Ottomans "were in Valladolid already", and used information technology as a way to obtain concessions from the Spanish crown.[28]

"William of Orange pledges his jewels for the defence of his land".

Contacts soon became more directly. William of Orange sent ambassadors to the Ottoman Empire for aid in 1566. When no other European power would help, "the Dutch crusade was offered active support, paradoxically enough, only by the Ottoman Turks".[28] I of the Sultan principal advisers Joseph Miques, Duke of Naxos, delivered a letter to the Calvinists in Antwerp pledging that "the forces of the Ottomans would soon striking Philip II's affairs so hard that he would not even have the time to think of Flanders".[29] The death of Suleiman the Magnificent later on in 1566 however, meant that the Ottoman were unable to offer support for several years after.[29] In 1568, William of Orange again sent a request to the Ottomans to assault Spain, without success. The 1566-1568 defection of the netherlands finally failed, largely due to the lack of foreign back up.[29]

In 1574, William of Orange and Charles IX of France, through his pro-Huguenot ambassador François de Noailles, Bishop of Dax, tried again to obtain the back up of the Ottoman ruler Selim II.[30] Selim II sent his support through a messenger, who endeavoured to put the Dutch in contact with the rebellious Moriscos of Spain and the pirates of Algiers.[30] [31] Selim also sent a bully fleet which conquered Tunis in October 1574, thus succeeding in reducing Spanish pressure on the Dutch, and leading to negotiations at the Conference of Breda.[thirty] After the death of Charles IX in May 1574 withal, contacts weakened, although the Ottomans are said to take supported the 1575-1576 revolt, and found a Consulate in Antwerp (De Griekse Natie). The Ottomans fabricated a truce with Espana, and shifted their attention to their conflict with Persia, starting the long Ottoman–Safavid War (1578–1590).[xxx]

The British author William Rainolds (1544–1594) wrote a pamphlet entitled "Calvino-Turcismus" in criticism of these rapprochements.[32]

The phrase Liever Turks dan Paaps ("Rather a Turk than a Papist") was a Dutch slogan during the Dutch Revolt of the end of the 17th century. The slogan was used past the Dutch mercenary naval forces (the "Body of water Beggars") in their fight confronting Cosmic Spain.[24] The banner of the Body of water Beggars was also similar to that of the Turks, with a crescent on a red background.[24] The phrase "Liever Turks dan Paaps" was coined as a manner to limited that life nether the Ottoman Sultan would have been more desirable than life nether the King of Spain.[10] The Flemish noble D'Esquerdes wrote to this effect that he:

would rather become a tributary to the Turks than alive against his conscience and be treated according to those [anti-heresy] edicts.

—Letter of Flemish noble D'Esquerdes.[10]

The slogan Liever Turks dan Paaps seems to have been largely rhetorical all the same, and the Dutch hardly contemplated life under the Sultan at all. Ultimately, the Turks were infidels, and the heresy of Islam alone butterfingers them from assuming a more central (or consistent) part in the rebels' program of propaganda.[10]

During the early on 17th century the Dutch trading ports housed many Muslims, according to a Dutch traveler to Persia at that place would exist no use in describing the Persians as "they are so numerous in Dutch cities". Dutch paintings from that time frequently show Turks, Persians and Jews strolling through the city. Officials that were sent to the netherlands included Zeyn-Al-Din Beg of the Saffavid empire in 1607 and Ömer Aga of the Ottoman Empire in 1614. Like the Venetians en Genoese before them, the Dutch and English established a trade network in the eastern Mediterranean and had regular interactions with the ports of the Persian Gulf. Many Dutch painters even went to work in Isfahan, central Iran.[33]

From 1608, Samuel Pallache served as an intermediary to discuss an alliance between Morocco and the Low Countries. In 1613, the Moroccan Ambassador Al-Hajari discussed in La Hague with the Dutch Prince Maurice of Orange the possibility of an alliance betwixt the Dutch Republic, the Ottoman Empire, Morocco and the Moriscos, confronting the mutual enemy Espana.[34] His volume mentions the give-and-take for a combined offensive on Kingdom of spain,[35] as well as the religious reasons for the good relations betwixt Islam and Protestantism at the fourth dimension:

Their teachers [Luther and Calvin] warned them [Protestants] against the Pope and the worshippers of Idols; they also told them non to hate the Muslims because they are the sword of God in the world against the idol-worshippers. That is why they side with the Muslims.

—Al-Hajari, The Volume of the Protector of Organized religion against the Unbelievers [35]

During the Thirty Years State of war (1618–1648), the Dutch would strengthen contacts with the Moriscos against Spain.[36]

French Huguenots and Islam [edit]

French Huguenots were in contact with the Moriscos in plans confronting Spain in the 1570s.[31] Around 1575, plans were made for a combined set on of Aragonese Moriscos and Huguenots from Béarn under Henri de Navarre against Spanish Aragon, in agreement with the king of Algiers and the Ottoman Empire, but these projects foundered with the arrival of John of Austria in Aragon and the disarmament of the Moriscos.[37] [38] In 1576, a three-pronged fleet from Constantinople was planned to disembark betwixt Murcia and Valencia while the French Huguenots would invade from the north and the Moriscos accomplish their uprising, but the Ottoman fleet failed to arrive.[37]

Brotherhood betwixt the Barbary states and England [edit]

Following the sailing of The Lion of Thomas Wyndham in 1551,[40] and the 1585 establishment of the English Barbary Company, trade developed between England and the Barbary states, and specially Kingdom of morocco.[41] [42] Diplomatic relations and an alliance were established between Elizabeth and the Barbary states.[42] England entered in a trading relationship with Morocco detrimental to Spain, selling armour, ammunition, timber, metal in exchange for Moroccan sugar, in spite of a Papal ban,[43] prompting the Papal Nuncio in Kingdom of spain to say of Elizabeth: "in that location is no evil that is non devised by that woman, who, it is perfectly plain, succoured Mulocco (Abd-el-Malek) with arms, and especially with artillery".[44]

In 1600, Abd el-Ouahed ben Messaoud, the main secretary to the Moroccan ruler Mulai Ahmad al-Mansur, visited England as an ambassador to the court of Queen Elizabeth I.[41] [45] Abd el-Ouahed ben Messaoud spent 6 months at the court of Elizabeth, in order to negotiate an brotherhood against Espana.[39] [41] The Moroccan ruler wanted the help of an English fleet to invade Spain, Elizabeth refused, but welcomed the embassy as a sign of insurance, and instead accepted to establish commercial agreements.[42] [41] Queen Elizabeth and king Ahmad continued to discuss various plans for combined armed forces operations, with Elizabeth requesting a payment of 100,000 pounds in advance to king Ahmad for the supply of a fleet, and Ahmad asking for a alpine send to be sent to get the coin. Elizabeth "agreed to sell munitions supplies to Morocco, and she and Mulai Ahmad al-Mansur talked on and off about mounting a joint functioning against the Spanish".[46] Discussions however remained inconclusive, and both rulers died inside two years of the embassy.[47]

Collaboration betwixt the Ottoman Empire and England [edit]

Diplomatic relations were established with the Ottoman Empire during the reign of Elizabeth, with the chartering of the Levant Company and the dispatch of the first English language ambassador to the Porte, William Harborne, in 1578.[46] Numerous envoys were dispatched in both directions and epistolary exchanges occurred between Elizabeth and Sultan Murad III.[18] In i correspondence, Murad entertained the notion that Islam and Protestantism had "much more than in mutual than either did with Roman Catholicism, as both rejected the worship of idols", and argued for an brotherhood between England and the Ottoman Empire.[xix] To the dismay of Catholic Europe, England exported tin can and lead (for cannon-casting) and ammunition to the Ottoman Empire, and Elizabeth seriously discussed joint armed services operations with Murad III during the outbreak of state of war with Spain in 1585, as Francis Walsingham was lobbying for a straight Ottoman military machine involvement confronting the common Spanish enemy.[48]

English writers of the period oft expressed admiration towards the "Turks" and the "Ottoman Empire", describing it as endowed with "Majestical and August form and features" and being the "Powerfullest nation in Europe", saying that the Turks were "the only modern people, swell in action- he who would behold these times in their greatest celebrity, could non find a better scene than Turky" and that they had "incredible civility".[49]

Anglo-Turkish piracy [edit]

After peace was made with Cosmic Kingdom of spain in 1604, English pirates yet continued to raid Christian shipping in the Mediterranean, this time under the protection of the Muslim rulers of the Barbary States, and often converting to Islam in the process, in what has been described as Anglo-Turkish piracy.[fifty] [51] [52]

Transylvania and Hungary [edit]

In eastern Central Europe, peculiarly in Transylvania, tolerant Ottoman dominion meant that the Protestant communities at that place were protected from Catholic persecutions by the Habsburg. In the 16th century, the Ottomans supported the Calvinists in Transylvania and Hungary and practised religious toleration, giving most complete freedom, although heavy taxation was imposed. Suleiman the Magnificent in particular supported John Sigismund of Hungary, allowing him to found the Unitarian Church in Transylvania. By the stop of the century, large parts of the population in Republic of hungary thus became either Lutheran or Calvinist, to become the Reformed Church in Republic of hungary.[11] [53]

The Hungarian leader Imre Thököly (1657–1705) requested and obtained Ottoman intervention to help defend Protestantism against the repression of the Cosmic Habsburg.

In the 17th century Protestant communities again asked for Ottoman help confronting the Habsburg Catholics. When in 1606 Emperor Rudolph II suppressed religious liberty, Prince István Bocskay (1558–1606) of Transylvania, centrolineal with the Ottoman Turks, achieved autonomy for Transylvania, including guaranteeing religious liberty in the rest of Hungary for a short time. In 1620, the Transylvanian Protestant prince Bethlen Gabor, fearful of the Catholic policies of Ferdinand II, requested a protectorate by Sultan Osman II, so that "the Ottoman Empire became the ane and but ally of great-power status which the rebellious Maverick states could muster after they had shaken off Habsburg rule and had elected Frederick V equally a Protestant rex",[54] Ambassadors were exchanged, with Heinrich Biting visiting Istanbul in January 1620, and Mehmed Aga visiting Prague in July 1620. The Ottomans offered a strength of sixty,000 cavalry to Frederick and plans were made for an invasion of Poland with 400,000 troops in exchange for the payment of an annual tribute to the Sultan.[55] The Ottomans defeated the Poles, which were supporting the Habsburgs in the Thirty Years' State of war, at the Boxing of Cecora in September–October 1620,[56] but were not able to farther intervene efficiently before the Bohemian defeat at the Boxing of the White Mountain in November 1620.[54]

At the end of the century, the Hungarian leader Imre Thököly, in resistance to the anti-Protestant policies of the Habsburg,[54] asked and obtained, the military machine help of the Ottoman Grand Vizier Kara Mustafa, leading to the 1683 Ottoman assault on the Habsburg Empire and the Battle of Vienna.[57]

In the 16th century Hungary had get almost entirely Protestant, with starting time Lutheranism, then shortly later on Calvinism, but following the Habsburg policy of Counter-Reformation the western part of the land finally returned to Catholicism, while the eastern part has managed to this day to remain strongly Protestant: "although the Habsburg succeeded in re-Catholicising Royal Hungary, east of the Tisza the Reformation remained almost intact in the spirit of peaceful coexistence between the three recognized nations and respect for their diverse creeds".[58]

Rich Protestant Transylvanian Saxon merchants traded with the Ottoman Empire and often donated Anatolian rugs to their churches as a wall ornamentation more according to their iconoclastic beliefs than the images of the saints used by the Catholics and the Orthodox. Churches similar the Black Church building of Brașov even so concur collections of rugs.

Relations with Persia [edit]

At about the same time England also maintained a pregnant human relationship with Persia. In 1616, a trade agreement was reached between Shah Abbas and the East India Visitor and in 1622 "a articulation Anglo-Western farsi force expelled the Portuguese and Spanish traders from the Persian Gulf" in the Capture of Ormuz.[59]

A grouping of English adventurers, led by Robert Shirley had a key role in modernizing the Persian army and developing its contacts with the Westward. In 1624, Robert Shirley led an embassy to England in order to obtain trade agreements.[sixty]

Later relations [edit]

The bombardment of Algiers past the Anglo-Dutch armada in support of an ultimatum to release European slaves, August 1816

These unique relations between Protestantism and Islam mainly took place during the 16th and 17th century. The ability of Protestant nations to disregard Papal bans, and therefore to establish freer commercial and other types of relations with Muslim and heathen countries, may partly explain their success in developing influence and markets in areas previously discovered by Spain and Portugal.[61] Progressively even so, Protestantism became able to consolidate itself and became less dependent on external help. At the same fourth dimension, the ability of the Ottoman Empire waned from its 16th century superlative, making attempts at brotherhood and conciliation less relevant. Notwithstanding, in 1796 the Treaty of Tripoli (between the U.s.a. and the Subjects of Tripoli of Barbary) noted "that no pretext arising from religious opinions shall ever produce an intermission of the harmony existing between the ii countries."

Eventually, relations between Protestantism and Islam have often tended to become conflicted. Protestant slaves were caused by Barbary pirates in slave raids on ships and past raids on coastal towns from Ireland to holland and the southwest of Uk, equally far due north as Iceland. On some occasions, settlements such as Baltimore in Ireland were abased following a raid, merely existence resettled many years later. Between 1609 and 1616, England lonely lost 466 merchant ships to Barbary pirates.[62] In the context of the United States, Protestant missionaries seem to have been active in portraying Islam in an unfavourable light, representing information technology as "the prototype of anti-Christian darkness and political tyranny", in a way that helped construct in opposition an American national identity as "mod, democratic and Christian".[63] Some famous Protestants have criticized Islam like Pat Robertson [64] Jerry Falwell,[65] Jerry Vines,[66] R. Albert Mohler, Jr.[67] and Franklin Graham.[68] [69] [70]

Comparative elements [edit]

Also the obvious differences between the ii religious, there are also many similarities in their outlooks and attitudes to faith (especially with Sunni Islam),[71] peculiarly in respect to textual criticism, iconoclasm, tendencies to fundamentalism, rejection of marriage as a sacrament, rejection of necessary penance by priests, and the rejection of monastic orders.

Textual criticism [edit]

Islam and Protestantism have in common a reliance on textual criticism of the Volume.[72] This historical precedence combines to fact that Islam incorporates to a sure extent the Jewish and Christian traditions, recognizing the same God and defining Jesus as a prophet, as well equally recognizing Hebrew prophets, thus having a merits to encompassing all the religions of the Volume.[72]

Iconoclasm [edit]

![]()

The rejection of images in worship, although more prominent in Islam, is a common signal in Protestantism and Islam. This was already extensively recognized from the earliest times, as in the correspondence between Elizabeth I of England and her Ottoman Empire counterparts, in which she unsaid that Protestantism was closer to Islam than to Catholicism.[74] This is also a bespeak developed by Martin Luther in On State of war against the Turk, in which he praised the Ottomans for their rigorous iconoclasm:

It is part of the Turks' holiness, likewise, that they tolerate no images or pictures and are even holier than our destroyers of images. For our destroyers tolerate, and are glad to have, images on gulden, groschen, rings, and ornaments; merely the Turk tolerates none of them and stamps nothing only letters on his coins.

Rich Protestant Transylvanian Saxon merchants traded with the Ottoman Empire and oftentimes donated Anatolian rugs to their churches as a wall ornament more than according to their iconoclastic beliefs than the images of the saints used by the Catholics and the Orthodox. Churches similar the Black Church of Brasov yet hold collections of such rugs.

Fundamentalism [edit]

Islam and Protestantism have in common that they are both based on a direct analysis of the scriptures (the Bible for Protestantism and the Quran for Islam). This can be assorted to Catholicism in which knowledge is analysed, formalized and distributed by the existing structure of the Church. Islam and Protestantism are thus both based on "a rhetorical commitment to a universal mission", when Catholicism is based on an international structure. This leads to possibilities of fundamentalism, based on the popular reinterpretation of scriptures by radical elements.[76] The term "fundamentalism" was first used in America in the 1920, to describe "the consciously anti-modernist wing of Protestantism".[77]

Islamic and Protestant fundamentalism likewise tend to be very normative of individuals' behaviours: "Religious fundamentalism in Protestantism and Islam is very concerned with norms surrounding gender, sexuality, and family unit",[77] although Protestant fundamentalism tends to focus on individual behaviour, whereas Islamic fundamentalism tends to develop laws for the community.[78]

The most notable trend of Islamic fundamentalism, Salafism, is based upon a literal reading of the Qur'an and Sunnah without relying on the interpretations of Muslim philosophers, rejecting the need for Taqlid for recognized scholars.[79] Fundamentalist Protestantism is similar, in that the 'traditions of men' and the Church Fathers are rejected in favor of a literalist interpretation of the Bible, which is seen every bit inerrant.[80] Islamic Fundamentalists and Protestant Fundamentalists ofttimes refuse contextual estimation. Another similarity with Protestantism and Salafism is criticism of saint veneration and conventionalities in the power of relics and tombs,[81] [82] and emphasis on praying to God alone.

Islamic Protestantism [edit]

Parallels accept regularly been drawn in the similar attitudes of Islam and Protestantism towards the Scriptures. Some trends in Muslim revival have thus been defined every bit "Islamic Protestantism".[83] In a sense "Islamization is a political movement to gainsay Westernization using the methods of Western civilisation, namely a form of Protestantism within Islam itself".[84]

Vitality [edit]

Islam and Protestantism share a common vitality in the modern earth: "The 2 most dynamic religious movements in the gimmicky world are what can loosely be called popular Protestantism and resurgent Islam", although their arroyo to civil order is different.[85]

See also [edit]

- Islam in England

- Protestantism in Turkey

- Protestantism in Pakistan

- Mormonism and Islam

- Islam and other religions

- Divisions of the world in Islam

- Pallache family

- Protestantism and Judaism

- Schmalkaldic League

- On State of war Against the Turk

Notes [edit]

- ^ a b Goody 2004, p. 42.

- ^ Nițulescu, Daniel (half-dozen May 2016). "The Influence of the Ottoman Threat on the Protestant Reformation (Reformers)". Andrews Research Conference . Retrieved 22 March 2021.

- ^ "Peace of Nuremberg". Oxford Reference . Retrieved 22 March 2021.

- ^ Grieve, Paul (7 February 2013). A Brief Guide to Islam: History, Faith and Politics: The Complete Introduction. The Development of Islam: Shi'a and Catholics: Hachette UK. ISBN9781472107558.

- ^ Allen, Jr., John Fifty. (ten Nov 2009). The Future Church: How Ten Trends are Revolutionizing the Catholic Church (unabridged ed.). Crown Publishing Group. pp. 442–three. ISBN9780385529532.

- ^ Smith, John MacDonald; Quenby, John, eds. (2009). Intelligent Religion: A Celebration of 150 Years of Darwinian Development (illustrated ed.). John Hunt Publishing. p. 245. ISBN9781846942297.

- ^ Rogerson, J. Due west.; Lieu, Judith One thousand. (xvi Mar 2006). The Oxford Handbook of Biblical Studies (reprint ed.). OUP Oxford. p. 829. ISBN9780199254255.

- ^ Hubbard-Brown, Janet (2007). Shirin Ebadi. Infobase Publishing. p. 47. ISBN9781438104515.

- ^ Coatsworth, John; Cole, Juan; Hanagan, Michael; Perdue, Peter C.; Tilly, Charles; Tilly, Louise A. (16 Mar 2015). Global Connections (illustrated ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 26. ISBN9780521761062.

- ^ a b c d Schmidt 2001, p. 104.

- ^ a b c d east Goffman 2002, p. 111.

- ^ a b Goffman 2002, p. 110.

- ^ a b Goffman 2002, p. 109.

- ^ Arand 2018, p. 167-169. sfn fault: no target: CITEREFArand2018 (help)

- ^ a b Miller, Roland East. (2005). Muslims and the Gospel: Bridging the Gap : A Reflection on Christian Sharing. Kirk House Publishers. p. 208. ISBN978-i-932688-07-viii.

- ^ a b Roupp, Heidi (26 December 1996). Teaching World History: A Resource Book. M.Due east. Sharpe. pp. 125–126. ISBN978-0-7656-3222-7.

- ^ a b c Karpat, Kemal H. (1974). The Ottoman Land and Its Place in World History: Introduction. BRILL. p. 53. ISBN978-ninety-04-03945-ii.

- ^ a b Kupperman 2007, p. 39.

- ^ a b c Kupperman 2007, p. 40.

- ^ a b Burton 2005, p. 62.

- ^ Andrea, Bernadette (17 January 2008). Women and Islam in Early on Modern English Literature. Cambridge Academy Press. p. 23. ISBN978-1-139-46802-2.

- ^ Burton 2005, p. 64.

- ^ Hassall, Arthur. Louis XIV Amp the Zenith of the French Monarchy. p. 224. ISBN978-0-543-96087-0.

- ^ a b c Bulut, Mehmet (2001). Ottoman-Dutch Economic Relations: In the Early Modern Catamenia 1571-1699. Northward.W. Posthumus reeks. Hilversum: Verloren. p. 112. ISBN978-90-6550-655-nine.

- ^ Goody 2004, p. 45.

- ^ a b Boxer, C.R; WIC (1977). The Dutch Seaborne Empire, 1600-1800. London: Hutchinson. p. 142. ISBN978-0-09-131051-6.

- ^ a b Schmidt 2001, p. 103.

- ^ a b Parker 1978, p. 59. sfn error: no target: CITEREFParker1978 (help)

- ^ a b c Parker 1978, p. lx. sfn error: no target: CITEREFParker1978 (help)

- ^ a b c d Parker 1978, p. 61. sfn mistake: no target: CITEREFParker1978 (help)

- ^ a b Kaplan, Benjamin J. (2007). Divided past Faith. Harvard University Press. p. 311. ISBN978-0-674-02430-4.

- ^ Knight, Kevin. "William Reinolds". Catholic Encyclopedia.

- ^ Verwantschap tussen de Perzische en Nederlandse cultuur Lecture on Persian-Dutch relations by Asghar Seyed Gohrab

- ^ Hillgarth, J. North. (2000). The Mirror of Spain, 1500-1700: The Germination of a Myth. University of Michigan Press. p. 210. ISBN978-0-472-11092-6.

- ^ a b Matar, Due north., ed. (2003). In the Lands of the Christians: Arabic Travel Writing in the Seventeenth Century. New York: Routledge. p. 37. ISBN978-0-415-93227-i.

- ^ Srhir, Khalid Ben (2005). United kingdom of great britain and northern ireland and Kingdom of morocco During the Embassy of John Drummond Hay, 1845-1886. RoutledgeCurzon. p. fourteen. ISBN978-0-7146-5432-4.

- ^ a b Lea, Henry Charles (one January 1999). The Moriscos of Spain: Their Conversion and Expulsion. Adegi Graphics LLC. p. 281. ISBN978-0-543-95971-3.

- ^ Harvey, 50. P. (15 September 2008). Muslims in Spain, 1500 to 1614. Academy of Chicago Printing. p. 343. ISBN978-0-226-31965-0.

- ^ a b Tate Gallery exhibition "E-West: Objects between cultures". Archived from the original on six July 2011.

- ^ Porter, Andrew N. (1994). Atlas of British Overseas Expansion. Routledge. p. xviii. ISBN978-0-415-06347-0.

- ^ a b c d Vaughan, Virginia Mason (12 May 2005). Performing Black on English Stages, 1500-1800. Cambridge University Press. p. 57. ISBN978-0-521-84584-7.

- ^ a b c Nicoll 2002, p. 90.

- ^ Bartels, Emily Carroll (2008). Speaking of the Moor: From Alcazar to Othello. Academy of Pennsylvania Printing. p. 24. ISBN978-0-8122-4076-4.

- ^ Dimmock, Matthew (2005). New Turkes: Dramatizing Islam and the Ottomans in Early Modern England. Ashgate. p. 122, note 63. ISBN978-0-7546-5022-5.

- ^ "Online Collections". University of Birmingham.

- ^ a b Kupperman 2007.

- ^ Nicoll 2002, p. 96.

- ^ Kupperman 2007, p. 41.

- ^ Suranyi, Anna (2008). The Genius of the English Nation: Travel Writing and National Identity in Early Modern England. Associated University Presse. p. 58. ISBN978-0-87413-998-three.

- ^ Dearest, Robert William (2001). New Interpretations in Naval History: Selected Papers From the Eleventh Naval History Symposium, Held at the Usa Naval University, 21-23 October 1993. Naval Institute Printing. p. 22. ISBN978-1-55750-493-seven.

The study of Anglo-Turkish piracy in the Mediterranean reveals a fusion of commercial and foreign policy interests embodied in the development of this special relationship

- ^ McCabe, Ina Baghdiantz (xv July 2008). Orientalism in Early Modern French republic: Eurasian Merchandise, Exoticism and the Ancien Regime. Berg. p. 86. ISBN978-1-84520-374-0.

At the beginning of the seventeenth century France complained well-nigh a new phenomenon: Anglo-Turkish piracy

- ^ Davis, Grace Maple (1911). Anglo-Turkish Piracy in the Reign of James I. Stanford University.

- ^ Stearns, Peter North. (2001). The Encyclopedia of World History: Ancient, Medieval, and Modern, Chronologically Bundled. Houghton Mifflin. p. 310. ISBN978-0-395-65237-4.

- ^ a b c Faroqhi, Suraiya (28 April 1997). An Economic and Social History of the Ottoman Empire. Cambridge University Printing. pp. 424–425. ISBN978-0-521-57455-6.

- ^ Pursell, Brennan C. (2003). The Winter King: Frederick five of the Palatinate and the Coming of the 30 Years' War. Ashgate. pp. 112–113. ISBN978-0-7546-3401-0.

- ^ Shaw, Stanford J.; Shaw, Ezel Kural (29 Oct 1976). History of the Ottoman Empire and Modern Turkey: Volume 1, Empire of the Gazis: The Rise and Reject of the Ottoman Empire 1280-1808. Cambridge Academy Press. p. 191. ISBN978-0-521-29163-seven.

- ^ Carsten, F. L. (1961). The New Cambridge Modern History: Volume 5, the Clout of France, 1648-88. Cup Archive. p. 513. ISBN978-0-521-04544-5.

- ^ Lendvai, Paul (2003). Die Ungarn: Ein Jahrtausend Sieger Und Niederlagen [The Hungarians: A Millennium Winners And Defeats] (in German). C. Hurst. p. 113. ISBN978-1-85065-682-1.

- ^ Badiozamani, Badi; Badiozamani, Ghazal (2005). Iran and America: Re-Kind[l]ing a Love Lost. East West Agreement Pr. p. 182. ISBN978-0-9742172-0-viii.

- ^ Maquerlot, Jean-Pierre; Willems, Michèle (xiii September 1996). Travel and Drama in Shakespeare's Time . Cambridge University Press. p. 17. ISBN978-0-521-47500-6.

- ^ Goody 2004, p. 49.

- ^ Rees Davies, "British Slaves on the Barbary Coast", BBC, ane July 2003

- ^ Hurd, Elizabeth Shakman (10 January 2009). The Politics of Secularism in International Relations. Princeton University Press. p. 59. ISBN978-one-4008-2801-2.

- ^ Tencer, Daniel (10 November 2009). "Pat Robertson: Islam isn't a religion; treat Muslims like fascists". Raw Story . Retrieved 7 February 2018.

- ^ Anti-Defamation League. "ADL Condemns Falwell'due south Anti-Muslim Remarks; Urges Him to Apologize". Archived from the original on 6 June 2008.

- ^ Cooperman, Alan (2010-04-28). "Anti-Muslim Remarks Stir Tempest". The Washington Post.

- ^ The O'Reilly Factor, Fox News Channel. March 17, 2006.

- ^ Pleming, Susan. "Muslims at Pentagon Incensed Over Invitation to Evangelist". Archived from the original on 21 March 2006.

- ^ Murphy, Jarrett (16 April 2003). "Pentagon'due south Preacher Irks Muslims". CBS News . Retrieved seven February 2018.

- ^ Starr, Barbara (18 April 2003). "Franklin Graham conducts services at Pentagon". CNN Within Politics . Retrieved 7 February 2018.

- ^ "Sectarian splits are widening in Islam and lessening in Christianity". The Economist. 27 Jan 2016. Retrieved 28 January 2016.

- ^ a b Yeʼor, Bat (2005). Eurabia-Cloth. Fairleigh Dickinson Univ Press. p. 221. ISBN978-0-8386-4076-0.

- ^ "History: The birth and growth of Utrecht". Domkerk, Utrecht. 12 January 2012. Archived from the original on 2012-01-12. Retrieved seven February 2018.

- ^ Matar, Nabil (13 October 1998). Islam in Britain, 1558-1685. Cambridge University Press. p. 123. ISBN978-0-521-62233-2.

- ^ Luther, Martin (one March 2007). Works of Martin Luther. Read Books. p. 101. ISBN978-ane-4067-7699-seven.

- ^ Fundamentalism. Polity. 2008. p. 101. ISBN978-0-7456-4075-iv.

- ^ a b Brzuzy, Stephanie; Lind, Amy (thirty December 2007). Battleground: Women, Gender, and Sexuality [ii Volumes]. ABC-CLIO. p. 488. ISBN978-0-313-08800-ane.

- ^ Bendix, Reinhard (8 April 1980). Kings or People: Ability and the Mandate to Rule. University of California Press. p. 47. ISBN978-0-520-04090-8.

- ^ "The Methodology of the Salaf Concerning Ijtihad and Taqlid". Salafi Publications.

Shaykhul-Islaam Ibn Taymiyyah, rahimahullaah, said: 'When a Muslim is faced with a problamatic situation, he should seek a verdict from ane whom he believes will requite him a verdict based upon what Allaah and His Messenger have legislated; whatever schoolhouse of thought (madhhab) he belongs to. It is not obligatory upon any Muslim to blindly follow a detail private from the scholars in all that he says. Nor is it obligatory upon any Muslim to blindly follow a particular madhhab from the scholars in all that it necessitates and informs. Rather, every person'south saying is taken or left, except that of the Allaah'due south Messenger sallallaahu alayhi wa sallam.'

- ^ Johnson, Phillip R. "The Chicago Argument on Biblical Inerrancy". Article I & XII. Archived from the original on 13 August 2012.

We affirm that the Holy Scriptures are to be received as the administrative Word of God. We deny that the Scriptures receive their authority from the Church, tradition, or whatever other human source...We assert that Scripture in its entirety is inerrant, being free from all falsehood, fraud, or deceit. Nosotros deny that Biblical infallibility and inerrancy are limited to spiritual, religious, or redemptive themes, exclusive of assertions in the fields of history and science. We further deny that scientific hypotheses almost earth history may properly exist used to overturn the teaching of Scripture on cosmos and the inundation.

- ^ says, Rashid Koja (2016-10-28). "Seeking blessings from the relics of the Prophets and the Pious; and visiting the places they visited as a ways of seeking nearness to Allah: by Abu Khadeejah". Salafi Sounds . Retrieved 2019-09-26 .

- ^ "A Treatise about relics of Jean Calvin (1543)". Musée protestant . Retrieved 2019-09-26 .

- ^ Ruthven, Malise (2006). Islam in the World. Oxford Academy Printing. p. 363. ISBN978-0-19-530503-6.

- ^ Turner, Bryan S. (1994). Orientalism, Postmodernism, and Globalism. Routledge. p. 93. ISBN978-0-415-10862-ane.

- ^ Juergensmeyer, Marking (3 November 2005). Religion in Global Civil Order. Oxford University Press. p. xvi. ISBN978-0-19-804069-nine.

References [edit]

- Burton, Jonathan (2005). Traffic and Turning: Islam and English language Drama, 1579-1624. Newark: University of Delaware Press. ISBN978-0-87413-913-6.

- Goffman, Daniel (2002). The Ottoman Empire and Early on Modern Europe . New approaches to European history. Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Printing. ISBN978-0-521-45280-9.

- Goody, Jack (2004). Islam in Europe . Cambridge, Britain: Polity Printing. ISBN978-0-7456-3192-9.

- Kupperman, Karen Ordahl (2007). The Jamestown Project. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Belknap Press of Harvard University Printing. ISBN978-0-674-02474-viii.

- Parker, Geoffrey; Smith, Lesley M., eds. (1978). The Full general Crisis of the Seventeenth Century. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul. ISBN978-0-7100-8865-9.

- Nicoll, Allardyce (2002). Shakespeare Survey With Index one-10. Cambridge Academy Press. ISBN978-0-521-52347-9.

- Schmidt, Benjamin (2001). Innocence Abroad: The Dutch Imagination and the New World, 1570-1670. Cambrdige, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN978-0-521-80408-0.

External links [edit]

- Wittenburg and Mecca issue of Logia: A Journal of Lutheran Theology

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Protestantism_and_Islam

0 Response to "The Muslims Fought Again Whom John Calvin"

Post a Comment